India’s setting up the Goods and Services Tax (GST) changed the process of simplifying indirect taxes. Many updates and improvements have been made to it since its July 2017 implementation. But as companies, customers, and legislators interact with the system, concerns about its complexity continue to arise. Could the GST structure in India be made simpler? This article examines the intricacies of the present GST framework and suggests future directions for a more straightforward and efficient system.

The Complexity of the Current GST Structure

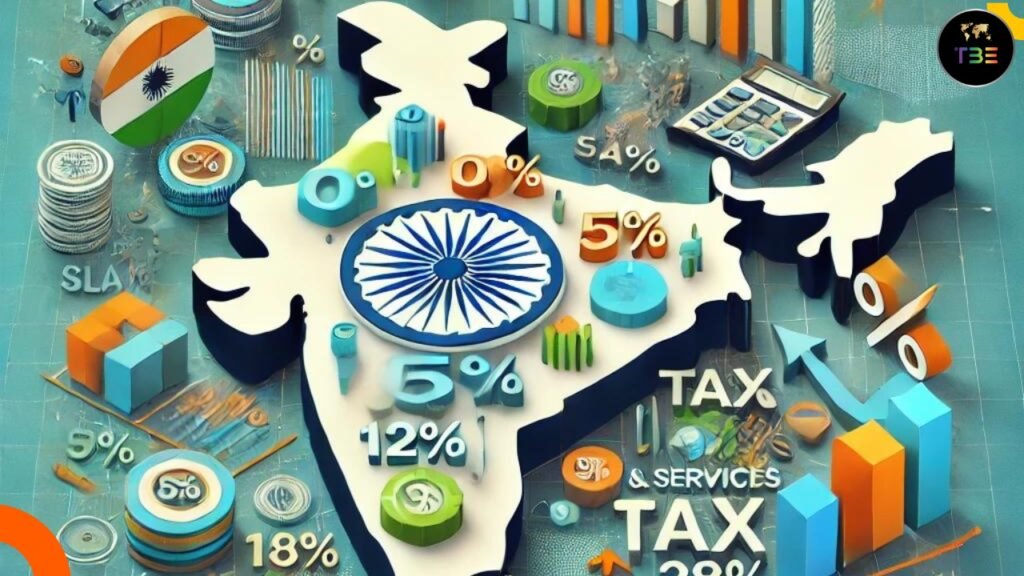

Fundamentally, the purpose of GST was to bring together different indirect taxes into a single tax, making compliance easier and minimizing the cumulative effect of multiple taxes. But the complex rate structure of the system, which has five main slabs (0%, 5%, 12%, 18%, and 28%), frequently causes misunderstandings and administrative difficulties. In addition to these tax rates, the procedure is made more difficult by a number of exemptions and the disparate treatment of items in comparable categories.

During a meeting with Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman, D Srinivasan, the Managing Director of Coimbatore’s Annapoorna Hotels, brought up the example of how a basic bun without cream is exempt from GST, but the same bun with cream is subject to 18% GST. It also draws attention to the larger problem of inconsistencies in the GST system.

The Effects of Different Tax Slabs

When similar goods are impacted by disparate tax rates, the complicated nature of the system is made clearer. A common example is the taxation difference between rotis and packed/frozen parathas; rotis are subject to a 5% GST slab, whereas parathas are subject to an 18% tax. Similar classification disputes arose over whether Marico’s Parachute hair oil should be taxed as coconut oil or hair oil.

Because these disputes increase the administrative burden and legal challenges, they are related to both tax authorities and businesses. These problems are made more serious by inconsistent tax rates on goods like shampoo, soaps, and sweets, which makes pricing and compliance more challenging for companies in all industries.

A Proposal to Justify GST Rates

The GST Council has worked to simplify the system during the previous six years. For example, the rates for body wash, shampoos, and soaps were set at 18% in November 2017. In a similar vein, the percentage for food and drink served in movie theaters was made clear and set at 5%, matching restaurant services.

Stakeholders, however, keep demanding more significant reform. The idea to combine the existing tax slabs into a three-tier structure is one of the most contentious. One option that could help clear up confusion and keep the government’s revenue neutrality is to combine the 12% and 18% slabs. The proposal does, however, present a number of obstacles, one of which is the possible loss of revenue, especially from the extremely profitable 18% slab, which accounts for almost 70% of GST collections.

Revenue-Related Factors

Any discussion regarding shifting the GST slabs still raises serious concerns about revenue neutrality. With an approximate 10% annual growth rate, the current GST collection has stabilized at about Rs 1.8 lakh crore per month. This revenue stream could be decreased by any changes made to the rate structure. For example, a modest decrease in the 18% slab to 17% might cause a large loss of revenue for the federal and state governments.

Although the weighted average GST rate fell to 11.6% by September 2019, the revenue-neutral rate was estimated in the Chief Economic Advisor’s report to be 15.3%. It is thought that the current rate is much lower. Finding a balance between the need for reduction and the need to protect sources of income is one of the GST Council’s most significant challenges.

Functions of Committees Specific to Industry

Creating officer committees with a focus on a particular industry is one way to potentially address the complexities of GST. Authorities may have gained a better understanding of the problems faced by various sectors by using this strategy during the initial implementation of GST. These committees could offer insightful commentary on how to improve the tax system without decreasing revenue collection or raising the cost of compliance for companies.

To lessen differences in tax stances adopted by various authorities, centralized audits and evaluations could also be implemented. The ease of doing business and tax certainty could be improved by a more standardized approach supported by industry tax position papers.

International Perspectives: Research from Other Nations

Observing other countries can provide interesting information about how India might improve its GST system. By successfully implementing flat GST rates with few deductions, nations like Singapore and New Zealand have made compliance easier for both tax authorities and businesses. Adopting a single-rate system is challenging in India due to its distinct economic and social structure, even though such a system might seem ideal.

In 2018, the late Finance Minister Arun Jaitley drew attention to the impossibility of a single-rate GST for an economy the size of India by drawing comparisons between the taxes levied on luxury goods like cars and essentials like food. Rather, he suggested setting up a three-slab system, with exceptions for luxury and sin goods, that would have rates of 0%, 5%, and standard.

The Path Ahead: Rationalization and Simplification of Rates

One thing is certain as the GST Council continues to discuss the system’s future: simplification is essential to guaranteeing the system’s long-term viability. Combining the 12% and 18% slabs might be one step toward simplifying things without suffering a significant drop in revenue. Legislators also need to make sure that similar products are taxed equally and address the inconsistencies that give rise to disputes over product classification.

Rates for consumer products, particularly those marketed by smaller producers, might be further rationalized. Simplified rates could help businesses maintain revenue neutrality while lowering the compliance burden on goods like biscuits, bakery products, and other B2C goods.

ALSO READ: Impact of BRICS: China and India Rule South Africa’s Automobile Import Market

Finding a Balance in Conclusion

There are two options for the Indian GST system. The country’s indirect tax system has been successful in unifying, but it continues to be restricted by its complexity and insufficient application. The first step in developing a more effective, business-friendly tax system is to simplify the rate structure and resolve classification issues. However, any modifications have to carefully balance the government’s revenue concerns against the need for simplification.

Politics and economy will be important considerations for the GST Council as it looks to the future. A more efficient system that facilitates compliance without sacrificing the government’s capacity to make money is what stakeholders from all sectors hope for. With the appropriate changes, other developing nations may look to India’s GST system as an example of how effective it can be.